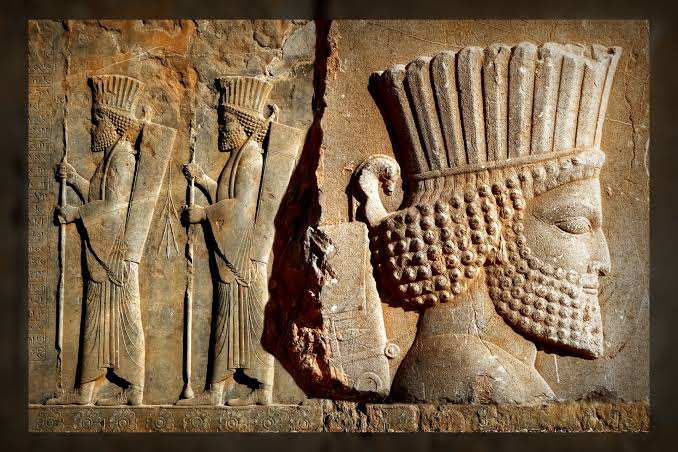

Greek historian Herodotus (484-425/413 BC), often criticized for inaccuracy in his Histories, he is frequently-anthologized. On the Customs of Persians is regarded as accurate. The passage is all more interesting in that he contrasts the behavior and values of Persians with those of Greeks with Persians shown in a much more flattering light. His depiction of Persians here is even more engaging when one considers how he presents Persian monarchs Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BC) and Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BC) as often-irrational tyrants and Darius I (r. 522-486 BC) as under the control of his wife elsewhere in his work.

Herodotus probably wrote his Histories when Persian king Artaxerxes I (r. 465-424 BC) was in power as work is thought to have been published 430-415 BC. Another interesting aspect of Persian passages as memory of Xerxes I’s invasion of Greece in 480 BC, would have still been fresh and Artaxerxes I, rejecting direct confrontation, was engaged in subtler means of bringing down Greek city-states. Even if one assumes that Herodotus knew nothing of Artaxerxes I’s various schemes, it would have been no secret that Persian Achaemenid Empire was no friend of Greeks at this time. Still, Herodotus consistently presents the Persians in a positive light even though, elsewhere, he clearly allows his personal feeling to color his depiction of an individual or event. First chapter (1.131), Herodotus claims Persians “have no images of the gods, no temples nor altars” and this has been challenged on grounds that Zoroastrian religion of Persians did include temples and altars but, it should be noted, these were by no means like temples and altars of Greeks. Rest of his description is entirely accurate as Zoroastrian fire temples were located on “summits of loftiest mountains” and other high places. He is also accurate in his description of birthdays as important annual events as Persians are known to have created practice of observing birthdays and also of instituting serving of desserts after a meal (I.133). Although claim has been challenged, he is also correct in his passage in same chapter on Persian love of wine and their policy of making decisions drunk and then reevaluating same when sober. Glowing description of Persians – who, he notes, think it “the most disgraceful thing in the world” to tell a lie (I.138) – is contrasted with the Greeks without Herodotus having to even mention his countrymen. Only time he specifically references Greeks is in I.135 when he says how Persians “have learnt unnatural lust from the Greeks.” There would have been no need for him to directly contrast Persian love of truth with Greek tendency to prevaricate because his audience would have been well aware of it and this same model holds true for rest of his description of Persian customs. Herodotus’ seemingly impartial and objective treatment of Persians is deceptive in that he seems to be quietly reminding his Greek audience of their own short-comings and perhaps reminding himself of the same, in believing themselves superior to other cultures. Scholar Robin Waterfield notes how Herodotus frequently uses antithesis to make a point without having to state it directly. Herodotus does this at a number of points throughout Histories but, as noted, his passage ‘On the Customs of the Persians’ is especially interesting given their relationship to Greece at the time he was writing. Criticisms of Herodotus’ work focus on his exaggerations or inaccuracies but there are many passages throughout which are not only reliable but reveal a sensibility and understanding in author that is not as apparent in every ancient historian.